Sections

Life’s fundamental division is twofold, into prokaryotes and eukaryotes. Prokaryotes are exclusively single-celled and consist of just a bag that encloses a watery fluid (the cytoplasm). In the fluid are millions of organic molecules (fats, proteins and carbohydrates), thousands of RNA molecules in ribosomes and a single large DNA molecule, usually in a convoluted loop (Figure 12.1a). A prokaryote can do only two things, but it does them well. It uses genetic coding in its DNA to replicate and form two smaller copies of itself, which then grow to reach the original size and it reproduces by cloning. The cell manufactures everything that it needs for replication, growth and repair inside itself, drawing energy and raw materials from its surroundings through its enveloping membrane.

Figure 12.1 Basic architecture of cells: (a) the prokaryote design; (b) a simple eukaryote animal cell. Plants also contain organelles called chloroplasts

Figure 12.1 Basic architecture of cells: (a) the prokaryote design; (b) a simple eukaryote animal cell. Plants also contain organelles called chloroplasts

The basic eukaryote cell (Figure 12.1b) is a barrel of fun by comparison with a prokaryote. It is still just a bag full of watery cytoplasm containing simple organic compounds and a little RNA, and it also draws in energy and raw materials through the cell wall. There the similarity ends. Eukaryote cells envelop a number of smaller bodies or organelles (‘little tools’, from the Greek). The most prominent of them is the nucleus surrounded by a double membrane, and therein lie DNA molecules bound together in chromosomes, whose antics form much of the basis both for sex and for the more familiar aspects of heredity and evolution. We return to those topics a little further on. Apart from the nucleus, a eukaryote cell may also contain such delights as the vacuole, two kinds of endoplasmic reticulum and the ominously named Golgi apparatus. On these we shall not dwell. Two other kinds of organelle are more important; the chloroplast (plants only) and the mitochondrion, which are enveloped, like the nucleus, by a double membrane.

Almost all eukaryotes have mitochondria in their cells, and it is these organelles that perform most of the conversion of raw materials to organic compounds on which the entire organism depends. The cells generate waste materials and can only function if oxygen is available. That is why virtually all eukaryotes, both plants and animals, are aerobic. There are a few that can only survive in oxygen-free environments such as animal guts and they lack mitochondria. One is Giardia and makes the world fall out of your bottom if you are unlucky enough to drink some types of polluted water. Only plant cells contain chloroplasts, and they perform photosynthesis, the simplest of all the kinds of metabolism among the eukaryotes. Chloroplasts use light as an energy source in assembling organic compounds from water and CO2, producing oxygen as a waste product. Both mitochondria and chloroplasts have their own complement of DNA, but not in a form that participates in eukaryote sex and the inheritance that stems from it. Such non-nuclear DNA is passed on to offspring, but the vast bulk of it comes from the female without mixing in half shares of DNA from the male, as happens to nuclear DNA during reproduction. So mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) is passed on from ‘mother’ to offspring in identical copies, except for random mutation. This makes mtDNA in animals like ourselves very useful in studying maternal relationships.

The vast diversity in form and ecological function of the eukaryotes, the most obvious members of the biosphere today, boils down to only two basic ways of life. On the other hand, the simple form of prokaryotes masks a far wider diversity of opportunities for living. Both eukaryotes and prokaryotes exploit laws of chemical combination and dissociation; and employ various sources of energy to do the work. The most familiar metabolism to us, simply because it is fundamentally what we do, is to build cells from complex organic molecules using them as a source of energy to do this. In other words we consume ‘food’ already made by other organisms. Such metabolisers are heterotrophs (‘nourishers from others’ in Greek). The other basic lifestyle is altogether more simple, by building organic molecules from scratch. The essential CHON and other elements are available in air, water and soils. Energy to combine them comes from inorganic sources too, principally the Sun, but also from simple chemical reactions. Metabolisers following this route are autotrophs (‘self-nourishers’). The most familiar autotrophs, and those that comprise most of the mass of the modern biosphere are green, photosynthesizing plants. They are at the base of the food chain of eukaryotes like us, who are heterotrophs whether we are vegans or not.

Bar a few loathsome forms, such as Giardia, all eukaryotes, hetero- or autotrophic, employ only one basic style of metabolism. They are aerobic, and depend on oxygen. The plant base of the eukaryote food chain uses sunlight as an energy source; it is photo-autotrophic. Here we temporarily leave the eukaryotes for a look at a much more basic chemistry of living, and at the amazing range of ways in which the lowly prokaryotes exploit quite simple chemistry.

Diversity built on chemistry

At the centre of the energy flows in metabolism are sugars (carbohydrates) of which glucose is the most universal. Sugars are simple molecules based on short chains of carbon bonded to hydrogen and oxygen – the three most common reactive elements in the cosmos. The simplest sugar molecule of all has one carbon, one oxygen and two hydrogens; it isn’t even a chain. Formaldehyde, or formalin, is not at all sweet and has a lugubrious use in storing cadavers. Put a spoonful of common salt in water containing formaldehyde, and lo and behold, out of corruption comes forth sweetness (NOT TO BE TRIED!). The HCOH (CH2O) formaldehyde molecules spontaneously link to form sugar chains, because alkali metal ions, such as sodium in the salt, act as catalysts for this polymerisation. The links can involve 2, 3, 4, 5 and 6 carbon atoms giving C2, C3, to C6 sugar chains. The C5 sugars or pentoses, ribose in particular, are vital building blocks in nucleic acids. Glucose and other better known sugars are of the C6 variety. Glucose is broken down to CO2 and water with the release of energy through the agency of a much more complex molecule, adenosine triphosphate or ATP. This is the most important store of useable energy for living things and it is worth examining what happens in more detail.

Two ATP molecules yield a phosphate ion to glucose and thus change to adenosine diphosphate ADP. These next combine to yield ATP and adenosine monophosphate AMP. The last is a nucleotide otherwise named adenine-deoxyribose-phosphate. Meanwhile, the phosphate-endowed glucose breaks down energetically to CO2 and water, releasing phosphoric acid, which combines with AMP to make ATP again. In this energy-releasing cycle ATP continually reforms. In the simplest sense possible, ATP is involved in self-replication, and it is lifelike in that respect, but that alone. One stage in the process, AMP, is linked to the structure of RNA and DNA, so this observation is not trivial.

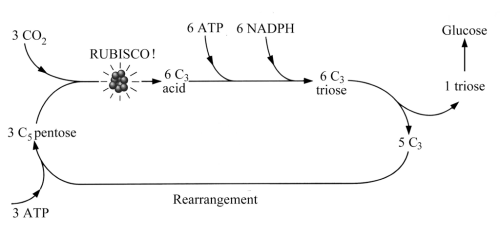

The foregoing begs the question of how sugars are formed in living things. Sugars are the intermediate step between the inorganic world of CO2 and H2O and that universe of complex CHONP molecules at the core of life. Fixing inorganic C, H, O, N and P etc. in life molecules is what eukaryote autotrophs do. There are several pathways, of which the most common today involves first the production of C3 chain molecules in photosynthesis. This is the Calvin (or C3) cycle (never to be confused with the Kelvin cycle involved in mechanical energy conversion) usually shortened to the. As Figure 12.2 shows, the C3 pathway depends on the intervention of ATP and two other arcane compounds, NADPH and Rubisco, the last not to be confused with a professorial tea-biscuit. Oh dear, NADPH is nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide which has a phosphoric addition and is hydrogenated. Rubisco is short for ribulose bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase (who would have guessed it?), an enzyme that happens to be the most abundant protein on this planet. Rubisco acts as the catalyst that enables pentose sugars to combine with CO2 thereby forming a C3 acid (left side of Figure 12.2), when ATP and NADPH intervene to form a C3 sugar (top) that partly polymerises to form the C6 sugar glucose (right).

Figure 12.2 Simplified model of how CO2 is fixed and glucose is produced by the Calvin or C3 cycle

Figure 12.2 Simplified model of how CO2 is fixed and glucose is produced by the Calvin or C3 cycle

We can break this bewildering complexity down to energy fundamentals of metabolism that involve very little chemistry other than those summarised by the mnemonic OILRIG (‘oxidation is loss, reduction is gain’ in terms of electrons). Electrons at a high energy level, which are associated with a chemically active molecule, atom or ion that readily donates electrons (a reducing agent), form the energy source for autotrophs. The transfer, in a series of steps, of electrons to molecules, atoms or ions that readily accept electrons (oxidizing agents), releases energy to power metabolism. Part of this energy drives or pumps hydrogen ions (H+ or protons) across the cell wall and membrane, thereby creating an electrochemical gradient or proton motive force (PMF). The PMF is constantly discharged back across the membrane by a reverse flow of protons that participate in the replication of ATP from ADP; a sort of proton pump. Donating and accepting electrons, and thereby generating a PMF can be accomplished by a wide variety of simple reactions some of which are employed by autotroph cells.

The most familiar type of autotrophy is that using light – photo-autotrophy or photosynthesis. Electrons are excited, or raised to a higher energy shell in an element or ion, by specific wavelengths of light according to Erwin Schrödinger’s wave theory (Chapter 3). In achieving this the compounds that generate the PMF selectively absorb these wavelengths, converting electromagnetic energy in the photons or quanta to that held in the new, excited electron shell. Those wavelengths that are not absorbed impart the colour to pigments employed in photo-autotrophy. Chlorophyll, which pigments green plants (eukaryotes, remember), uses blue and red light leaving only the green part of the solar spectrum to be reflected and perceived by our eyes as colour. There are other photosynthetic pigments coloured red and purple among the prokaryotes. Electrons excited in this way confer reducing properties on the pigment compounds – it is easier for them to be donated – and they are transferred to electron carriers that have oxidizing properties. The charge balance on the pigment must therefore be restored by a return supply of electrons. This is possible through two basic schemes, both of which are employed in prokaryote photosynthesis (Figure 12.3).

Figure 12.3 Two schemes for electrons energised by photo-autotrophy: (a) electrons transferred by carriers back to the light-absorbing pigment; (b) electrons lost to an internal acceptor are replaced in the pigment by external electron donors. In both cases a proton-motive force ensues

Figure 12.3 Two schemes for electrons energised by photo-autotrophy: (a) electrons transferred by carriers back to the light-absorbing pigment; (b) electrons lost to an internal acceptor are replaced in the pigment by external electron donors. In both cases a proton-motive force ensues

In one scheme electrons return to the pigment molecule in a less excited state, through simple recycling after pumping protons (Figure 12.3a). In the other they are accepted by an intermediary agent NAD+ that then attracts protons to become NADH, itself a source of reducing power, as is its phophorylated form NADPH (Figure 12.3b). As you saw earlier, this compound is implicated in the C3 fixation cycle, and many reactions that synthesise organic compounds require reducing power. Either a donor compound outside the cell or internal recycling resupplies electrons to the pigment.

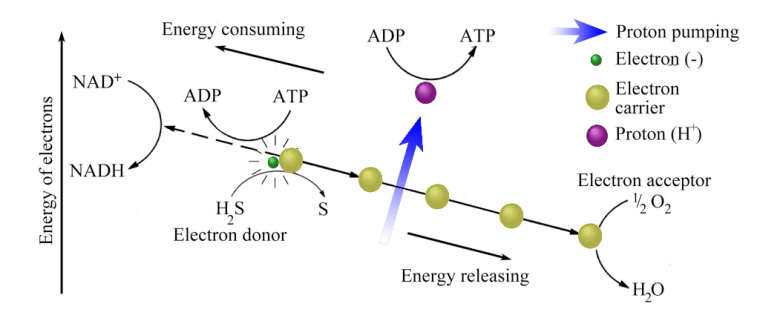

Photo-autotrophy depends for reducing power only on a light source, a pigment capable of becoming a reducing agent, and sometimes an external electron donor. However, simpler reducing agents are common in the inorganic chemical world. They include: hydrogen; sulfur; sulfides of metals and hydrogen sulfide; ferrous (Fe2+) iron and ammonium (NH4+) ions. The prokaryote world includes a whole range of simple organisms, for which these reducing agents provide the potential for generating energy flows. These are chem-autotrophs. Figure 12.4 shows one such scheme. Hydrogen sulfide gas is the electron donor, although a metal sulfide can serve just as well. Having donated an electron to carriers in the cell membrane, H2S is oxidised to sulfur, and pumped protons participate in the ADP to ATP conversion. At the low-energy end of the electron flow oxygen is reduced to water, so the overall chemistry used by such a prokaryote chemo-autotroph is summarised by the equilibrium:

H2S + 1/2O2 = H2O + S

In the same scheme electrons are driven in an energetically ‘uphill’ direction (left side of Figure 12.4) to reduce NAD+ or NADP+ to NADH or NADPH, and thereby ensure the fixing of CO2 in organic compounds.

Figure 12.4 Electron flow and proton pumping in chemo-autotrophy based on hydrogen sulfide

Figure 12.4 Electron flow and proton pumping in chemo-autotrophy based on hydrogen sulfide

Chemo-autotrophy provides prokaryote life a rich diversity of opportunity of which most of us eukaryotes are barely aware, for it occurs in places where we could not survive; generally where there is neither oxygen nor light. There are so many chemical reducing and oxidizing opportunities that, at first glance, it seems hard to believe that life on the planet is not completely overwhelmed by prokaryote ecosystems, instead of its mastery by the eukaryotes. There is one fundamental reason why this is not so today. Oxygen, the most common oxidizing agent, abundant in the air, the seas and the soil, wipes out the free availability of reducing agents in the largest environments, and with it much of the potential for chemo-autotrophy. As you saw in Part 2, this was not always the case, and free oxygen has become more abundant as geological time has passed by. There is a fascinating link between oxygen, and various lifeforms that have come into being, flourished, died out or evolved. That linkage forms a central theme to much of Part 4, crops up in later Parts, and, as you will discover, has an influence that extends to the very core of the planet.

Autotrophs, the primary producers in any ecosystem, are consumed in some way by heterotrophs. The metabolism of heterotrophs centres on the breaking of bonds in complex organic molecules, and that needs energy. As in autotrophy, energy is generated by electron transport and proton pumping. Likewise, heterotroph metabolism involves electron donors (reducing agents) and acceptors (oxidizing agents). Today oxygen is a widely available electron acceptor and all eukaryote heterotrophs use it in aerobic respiration. So too do some prokaryotes, but as in the case of their autotrophic food items, other kinds exploit many more chemical opportunities. Lots of prokaryote heterotrophs thrive in oxygen-poor conditions. Some use SO42+ (sulfate) ions dissolved in water as electron acceptors and reduce them to H2S. You, and more particularly those close to you, may become acutely aware of some that live in your gut, if you drink water containing abundant sulfate ions! A wide variety reduce nitrate (NO3–) to nitrite (NO2–) ions, and are the source of nitrite pollution from over-manured fields. Other electron acceptors exploited by prokaryotes include: ferric (Fe3+) iron; organic molecules, such as acetates (accounting for the bacteria that ‘eat’ plastics); and even CO2 that is reduced to methane (another prokaryote product of our gut). A few prokaryote heterotrophs avoid the need for proton pumping and thereby free themselves from the need for an electron acceptor. These are fermenting bacteria, whose metabolism involves only the transfer of phosphate from ATP to glucose to form ADP then AMP, which takes up phosphate again from the final breakdown of glucose to return to ATP. Fermenting is an inefficient style of heterotrophy, to which some prokaryotes can turn when their normal electron acceptor is in short supply. Exclusive fermenters are suspected of being among the most primitive life forms still in existence.

The foregoing is a most abbreviated account of the great complexity and variety of primary carbon fixation by autotrophs and respiration by heterotrophs. It is sufficient in our context to conclude that all metabolic pathways involve the movement of electrons and protons. As a result, all are dependent on the fundamental chemical processes of oxidation and reduction, together with the variation in hydrogen-ion concentration that governs whether an environment is acid or alkaline. These governing factors are expressed by the redox potential (Eh) that measures an environment’s ability to donate or accept electrons, and its pH, respectively. The simplified equilibrium:

CO2 + H2O + energy = HCOH + O2

may proceed to the right or to the left (Equations 3.1 and 3.2 in Chapter 3, where C-fixation and its role in the carbon cycle were introduced) are reducing and oxidizing reactions, respectively. How organisms function biochemically can be divided into a number of basic metabolic processes that are conditioned by environments with different Eh and pH. To some extent the concentration of various simple ions that result from the solution in water of inorganic salts, such as NaCl and CaSO4, also play a role. Such ions in the environment have an important bearing on how protons are pumped across cell membranes, at the root of all metabolic biochemistry, except that involved in fermentation. Fortunately, as outlined in Chapter 8, the rock record preserves features that signify in a general way the Eh and pH, and water composition of past environments. These help geologists to arrive at some sensible conclusions about interplays between the inorganic part of environments and the life forms that occupied them, and about their co-evolution.

A hidden empire

Having taken a brief trip into some chemistry at the cell level, we can now go on to look at some of the living prokaryotes. Until the late 1970s, prokaryotes posed great problems to taxonomists. In 1980 molecular biologists showed that the genetics of three groups of them differed so fundamentally from all other prokaryotes that the superficially simple organisms previously called Bacteria needed to be split into two domains standing above the level of Linnaeus’s kingdom. The Archaebacteria and the Eubacteria, now called the archaea and bacteria, have equal taxonomic status to all the eukaryotes, now the eukarya

The archaea include two main groups, plus some oddities (Figure 12.5). Some exist only in very hot water in springs around volcanoes and in hydrothermal vents on the sea floor. Most of these extreme thermophiles (heat lovers) are heterotrophs that use sulfur as an electron acceptor through SO4– to H2S reduction. They are important in encouraging the precipitation of metal sulfides in ‘black smokers’ when metal ions in the hot water encounter biogenic H2S. Sulpholobus uses H2S as an electron donor in acidic, almost boiling hot springs to fix CO2 in a unique way. It is a chemo-autotroph. These are the Crenarchaeota (formerly Sulfobacteria), but such is the novelty of dividing up prokaryotes along genetic lines that another chemo-autotroph is, for the moment, lumped with them – Pyrodictium, which uses the reducing properties of hydrogen gas as an energy source.

Figure 12.5 Division of the archaea based on the dissimilarity of their ribosomal RNA (rRNA), with a few example genera. Groups with affinities for hot water show as bold lines. Note nomenclature of the archaea is still fluid, so old group names are used.

Figure 12.5 Division of the archaea based on the dissimilarity of their ribosomal RNA (rRNA), with a few example genera. Groups with affinities for hot water show as bold lines. Note nomenclature of the archaea is still fluid, so old group names are used.

The Methanogens mainly inhabit oxygen-free swamps, airless soil layers and the guts of animals. Oxygen is deadly for Methanogens. Like Pyrodictium, they are chemo-autotrophs using hydrogen gas as an electron donor and energy source to fix carbon from CO2, though not through the Calvin cycle. Their waste products are methane and water, and account for the eery ‘Will o’the wisp’ flames occasionally seen in swampland. Included with the Methanogens (in the Euryarchaeota) because of genetic similarities are prokayotes that were formerly known as Halobacteria that thrive in very saline environments, such as evaporating lakes and even salt pork. Perversely, most Halobacteria are aerobic heterotrophs, and contain their own oddities. One has patches of a purple pigment that enable it to be a photosynthetic autotroph. This pigment is chemically very similar to rhodopsin found in the rod photoreceptors of the human retina that enable vision in low light levels. Other Halobacteria are anaerobic fermenters. One, Thermoplasma, has no cell wall, and contains DNA with proteins like those that bind nucleic acid in the nuclei of eukaryote cells. It lives in burning coal heaps. Thermoplasma depends on highly acid conditions brought about by the breakdown to sulfuric acid of iron sulfide (pyrite or ‘fool’s gold’) in the coal. Distanced genetically from the two main groups of archaea are a few that appear to be transitional between them; the domain archaea is perpetually in a taxonomic state of flux

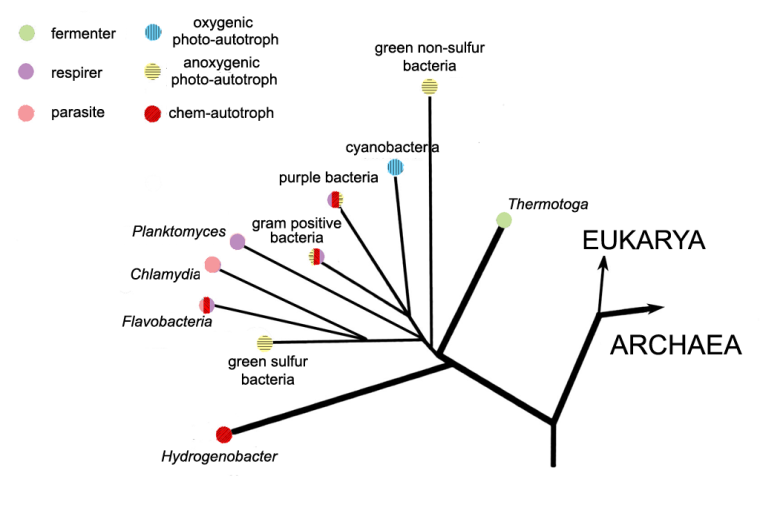

Diverse as the archaea seem, in terms of their ecological niches they pale into insignificance compared with the bacteria (Figure 12.6). They include groups of heterotrophs that can be aerobic or anaerobic, fermenters, chemo-autotrophs, photo-autotrophs, some combining several basic metabolic processes in twos or threes, and even parasitic forms that use ATP acquired from their hosts. One of the last is Chlamydia. It causes non-specific urethritis, a sexually transmitted disease.

Figure 12.6 Simplified genetic relatedness and lifestyles of some bacteria including two thermophilic genera (bold lines).

Figure 12.6 Simplified genetic relatedness and lifestyles of some bacteria including two thermophilic genera (bold lines).

Five groups of bacteria function as photo-autotrophs, four of which use one or other of the processes shown in Figure 12.3, infest anaerobic environments and produce no oxygen. Indeed, oxygen is lethal to them. The fifth group, Cyanobacteria (blue-green bacteria) are very different. They once assumed supreme importance in the history of the Earth’s biosphere, atmosphere and lithopshere So much so that we must dwell a while on the basic chemistry of their metabolism. Figure 12.7 shows the photosynthetic electron flow in Cyanobacteria cells. It is very different from the two photosynthetic schemes shown in Figure 12.3 and, instead of one, uses two reactions to light in tandem that excite electrons in two pigments (different forms of chlorophyll, which is built on a magnesium ‘core’). Both absorb part of red light, so giving the distinctive blue-green or cyan colour to the pigment. The lower energy excitation requires simply water as an external electron donor and generates free oxygen in the process. That requires a very powerful oxidizing agent involving the metal manganese (Mn), deployed by blue-greens in one of their chlorophyll pigments. No other photo-autotrophs can do that. But to reduce NADP+ to NADPH and thereby fix CO2, as all autotrophs must do somehow, demands an equally powerful set of reducing condition to produce sufficiently energetic electrons. Blue-greens achieve this with the other chlorophyll pigment using an iron-sulfur Rieske protein as an electron acceptor. In this respect blue greens seem to combine chemical aspects of the processes found in two other groups of photo-autotrophic bacteria, the green-sulfur bacteria and purple bacteria. Like the latter, blue-greens also use the Calvin cycle to reduce CO2 to carbohydrates. In short, blue-greens use a mix of anaerobic ‘chemical engineering’, produce oxygen that is fatal to anaerobes, yet somehow survive! The key to their success lies in their unique ability among the prokaryotes to use the most plentiful commodity on the Earth’s surface, water, as an electron donor. They also need a supply of soluble ferrous (Fe2+) iron, once abundant in the oceans before the Great Oxidation Event (Chapter 8) and now a micro-nutrient in surface seawater. Other external electron donors are only plentiful in relatively restricted geological sites. However and whenever they evolved, the blue-green Cyanobacteria found themselves with a huge potential living space, the oceans, provided the water was lit by the Sun. The oceans would be a large sink for the blue-greens’ toxic waste product, oxygen, thereby giving their ancestors a measure of protection from their own excreted oxygen.

Figure 12.7 Electron flow in blue-greens (Cyanobacteria) involves two forms of the pigment chlorophyll to give a double photosynthetic boost to the energy of electrons. One breaks down water, the other employs an Fe-S based Rieske protein. Both light wavelengths are reddish, so their absorption gives Cyanobacteria their distinctive blue-green colour. Symbols as in Figure 12.3.

Figure 12.7 Electron flow in blue-greens (Cyanobacteria) involves two forms of the pigment chlorophyll to give a double photosynthetic boost to the energy of electrons. One breaks down water, the other employs an Fe-S based Rieske protein. Both light wavelengths are reddish, so their absorption gives Cyanobacteria their distinctive blue-green colour. Symbols as in Figure 12.3.

Continuing the prokaryote story from the standpoint of comparisons between the molecular biology of modern representatives and ideas of evolutionary linkages must await the next chapter. We have neglected our kin for too long, so return to the eukaryote cell immediately.

Cohabitation and the eukarya

The preceding superficial tour of prokaryote diversity and their metabolic chemistry allows us to review the architecture of eukaryote cells from a new standpoint. When the American biologist Lynn Margulis did this in 1967, she developed an idea that had languished in the ‘haunted wing’ of cell biology since the early 20th century. Her resurrection with supporting evidence from microbiology, initially startled her colleagues. The various organelles within eukaryote cells (Figure 12.1), particularly mitochondria and chloroplasts, looked to her like prokaryote cells themselves. Both contain DNA, but not in a form that can participate in the sexual division that characterises eukaryotes. Both have a double membrane separating them from the eukaryote cytoplasm, which may be their own cell membrane plus an addition from the eukaryote cell. In fact, both have almost independent functions. Chloroplasts perform aerobic photosynthesis in plants, and mitochondria are the main chemical factories in all eukaryote cells bar a few oddities. Margulis’s idea was that both originated as independent prokaryotes. Indeed, chloroplasts are very like blue-green bacteria and mitochondria are similar to a number of living aerobic, heterotrophic bacteria. Leaving aside the eukaryote nucleus, other organelles and the common tail in single-celled eukaryotes, the rest of the cell is more or less a prokaryote itself. So how might such a hypothesised ‘club’ of prokaryotes have got together?

The simplest guess would be that they represent a sort of mutual association, a product of symbiosis. There are countless analogies, from the brave little fish that pick flesh from the teeth of Great White Sharks, the lobster’s lip creature, a whole army of prokaryotes and eukaryotes in and upon our own bodies, to single-celled heterotrophic eukaryotes that are stuffed with green algae cells that are protected by and provide food for their host. The last is endosymbiosis, and this is the core of Margulis’ theory. Figure 12.8 outlines two variants of her original scheme.

Figure 12.8 Lynn Margulis’s two endosymbiotic routes to the basic eukaryote ‘animal’ cell from a prokaryote ancestor. One engulfs aerobic bacteria to serve as mitochondria, to be joined later by whatever formed the nucleus and the flagellum that confers mobility. The other route delays mitochondria until after formation of the nucleus and flagellum. Incorporating cyanobacteria-like prokaryotes forms chloroplasts within the basic architecture and the ancestor of the plant kingdom.

Figure 12.8 Lynn Margulis’s two endosymbiotic routes to the basic eukaryote ‘animal’ cell from a prokaryote ancestor. One engulfs aerobic bacteria to serve as mitochondria, to be joined later by whatever formed the nucleus and the flagellum that confers mobility. The other route delays mitochondria until after formation of the nucleus and flagellum. Incorporating cyanobacteria-like prokaryotes forms chloroplasts within the basic architecture and the ancestor of the plant kingdom.

The original host may have been an anaerobic prokaryote fermenter surrounded by a flexible membrane rather than a cell wall; arguably a primitive characteristic. Smaller, oxygen-respiring bacteria entered the host, probably to use some of the end products of fermentation, but in turn supplying their host with chemicals that they produced. Exchange of genetic material between host and ‘guests’ – a characteristic of some prokaryotes – cemented the relationship. Much the same process would account for chloroplasts, except the bacteria that became endosymbionts must have been aerobic photo-autotrophs, of which blue-greens are the most obvious candidate. Because both animals and plants contain mitochondria, it seems reasonable to assume that chloroplasts developed later to source the plant kingdom. The self-moving ability of single-celled eukaryotes, using their little flagellum, seems superficially easy to address in the endosymbiont theory. There are whip-like bacteria called spirochaetes, but equally such tails may have been produced by the prototype eukaryote itself. There are selection advantages in being able to move, and far more strange things have been evolved by the eukaryotes than a whip-like tail. The thorniest problem is the nucleus and its DNA-based chromosomes; the real hallmark of eukaryotes, and, as you will see in Chapter 14, the source of their later success.

Since no living prokaryote has chromosomes, an endosymbiotic origin for the nucleus seems highly unlikely. One suggestion is that it arose by infolding of the host’s cell membrane to enclose the loops of DNA that typify prokaryote genetic material. The loops – which may have been the host’s genetic material or that of symbionts – somehow became transformed to chromosomes, with all the potential that they confer.

Like many potent ideas, the Margulis endosymbiotic theory for the origin of the eukaryote cell from successive incorporation of earlier prokaryote cells offers an explanation for the previously inexplicable. It may prove to be completely wrong, but many evolutionary biologists support it today, in one form or another. If nothing else, it gives us a framework within which to assemble information in a more or less manageable way. It also gives a simple order to events, yet to be tested, that eukaryotes evolved from prokaryotes. So if we are looking for the earliest forms of life, or rather the least-evolved descendants from the first life on Earth, the focus has to be within the prokaryotes. In Chapter 14 we look at some of the genetic evidence from modern organisms that helps clarify these roots. That takes us back to some idea of primitive life. The next big topic approaches the issue from another direction, by examining ideas about how truly living things could have been produced by completely inorganic processes.

Check out Further Reading for Part IV to see source material and links to articles

If you enjoyed reading this chapter online and want to learn more, Stepping Stones is available to download as an eBook